A broad body of literature anticipates that in the years to come intelligent objects will overtake more and more jobs that people have traditionally performed, from driving, diagnosing diseases, providing translation services, drilling for oil, to even milking cows, to name just some examples.

In 1999 a British visionary Kevin Ashton coined the term ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT) to describe a general network of things linked together and communicating with each other as computers do today on the Internet. The connection of objects to the Internet makes it possible to access remote sensor data and to control the physical world from a distance. Data communication tools are changing ‘tagged things’ into ‘smart objects’ with sensor data supporting a wireless communication link to the Internet.

With IoT manufacturers can remotely monitor the condition of equipment and look for indicators of imminent failure outside normal limits (e.g., vibration, temperature and pressure). This means that the manufacturer can make fewer visits, reducing costs and producing less disruption and higher satisfaction for the customer. Remote diagnostics, where complex manufactured products are monitored via sensors may not, however, only be important for repairing industrial machines but also for human health, such as remote control of pacemakers.

The widespread use of WiFi and 4G enable the communication with smart objects without the need of a physical connection, such as to control customers’ home heating and boiler from their mobile or laptop. Mobile smart objects can move around and GPS makes it possible to identify their location.

This technology facilitates the development of so-called connected or automated cars that enable the driver automatic notification of crashes and speeding, as well as voice commands, parking applications, engine controls and car diagnosis. It is foreseen that trucks will soon no longer need drivers, as computers will drive them, without the need for rest or sleep. Moreover, each Philips or Samsung TV comes nowadays with an application called ‘Smart TV’, which consolidates video on demand function, the Internet access, as well as social media applications. Objects are thus becoming increasingly smart and consequently autonomous.

……………………………………………………..

Matjaž Perc, Mahmut Ozer & Janja Hojnik

Abstract:

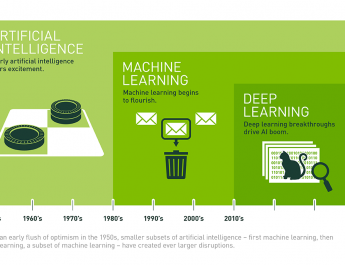

Artificial intelligence is becoming seamlessly integrated into our everyday lives, augmenting our knowledge and capabilities in driving, avoiding traffic, finding friends, choosing the perfect movie, and even cooking a healthier meal. It also has a significant impact on many aspects of society and industry, ranging from scientific discovery, healthcare and medical diagnostics to smart cities, transport and sustainability.

Within this 21st century ‘man meets machine’ reality unfolding, several social and juristic challenges emerge for which we are poorly prepared. We here review social dilemmas where individual interests are at odds with the interests of others, and where artificial intelligence might have a particularly hard time making the right decision. An example thereof is the well-known social dilemma of autonomous vehicles.

We also review juristic challenges, with a focus on torts that are at least partly or seemingly due to artificial intelligence, resulting in the claimant suffering a loss or harm. Here the challenge is to determine who is legally liable, and to what extent. We conclude with an outlook and with a short set of guidelines for constructively mitigating described challenges.